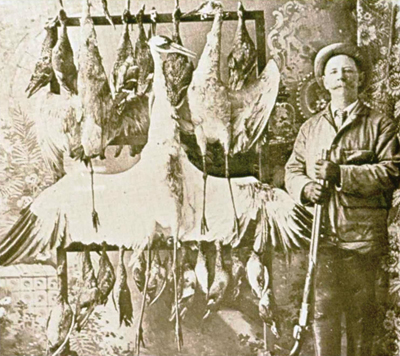

We estimate that in the mid-1800s there were around 1,200 to 1,500 Whooping Cranes in North America. By the early 1900s, Whooping Crane numbers had plummeted, and the species had disappeared from the heart of their historic breeding range in the north-central United States.

What caused this rapid decline? The cranes’ wetland breeding grounds were altered and disturbed as settlers plowed the native prairies and drained marshes for farming. Whooping Cranes also were hunted and their eggs collected, leading to increasing pressure on an already small population.

In 1918 the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act made it illegal to hunt Whooping Cranes. Despite this and other early protection efforts the Whooping Crane population continued to decline. By the late 1930s, only two small flocks remained — one non-migratory flock in Louisiana and one migratory flock that wintered in southeastern Texas and summered in western Canada. In 1940 a hurricane decimated the already small Louisiana population, and the number of Whooping Cranes in the wild dropped to just 21 birds by the mid-40s. In 1950 the last individual in the Louisiana population, “Mac,” was removed from the wild, leaving all remaining Whooping Cranes in the migratory flock that now numbered 34 birds.

Because of the critically low number of Whooping Cranes in the wild, biologists proposed increasing the population through captive breeding programs. The alternative was possible extinction. Beginning in 1967, eggs were transferred from the remaining breeding grounds at Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center near Laurel, Maryland. The captive Whooping Cranes at Patuxent first produced eggs in 1975, and gradually the captive flock at Patuxent grew.

In 1989, the U.S. and Canadian Whooping Crane Recovery Teams made the decision to split the captive flock and send 22 Whooping Cranes to the International Crane Foundation. Today, we have 44 captive Whooping Cranes at our headquarters and produce chicks each year for reintroduction into the wild and genetic management of the species. Learn more about our captive breeding and reintroduction programs.

WHOOPING CRANE

RECOVERY PLAN

In 1986, the Whooping Crane Recovery Plan was first developed to chart a course for saving the species from extinction. The plan was created by the Whooping Crane Recovery Team, a group of crane biologists and officials from the United States and Canada. If the recovery plan is successful, Whooping Cranes could be down-listed from endangered to threatened status by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

![]() Historic Whooping Crane Numbers

Historic Whooping Crane Numbers