Understanding Renesting in the Whooping Crane Eastern Migratory Population

Our Whooping Crane Field Team monitor an active nest in Wisconsin. International Crane Foundation photo

Whooping Cranes, like many long-lived bird species, are slow to reproduce, laying only two eggs in each nest and typically raising only one offspring every year. Like all crane species, Whooping Cranes mate for life and take selecting a life partner seriously. It takes Whooping Cranes at least 3-5 years to reach reproductive age and choose a mate. For crane species, it is important that the bonds between mated pairs are strong. Whooping Crane pairs will dance and unison call to reinforce and strengthen these bonds. In early spring, cranes will mate and build nests in the wetlands.

There are times, however, when a pair’s nest fails and they may build a new nest and lay another clutch of eggs, which is known as renesting. Renesting typically occurs when a nest fails early in the season, which can happen for a variety of reasons. Some of the most common reasons a nest may fail include predation of the eggs, flooding of the nesting area, or the cranes abandon the nest due to external factors such as parasitic black flies. Renesting gives Whooping Cranes another chance to hatch their eggs and raise a chick, without having to wait until the next year. This then begs the question: How can we better understand renesting behavior and the potential it plays in maximizing the breeding season for this endangered species?

A male Whooping Crane defends its nest from a predator. Tran Triet/International Crane Foundation

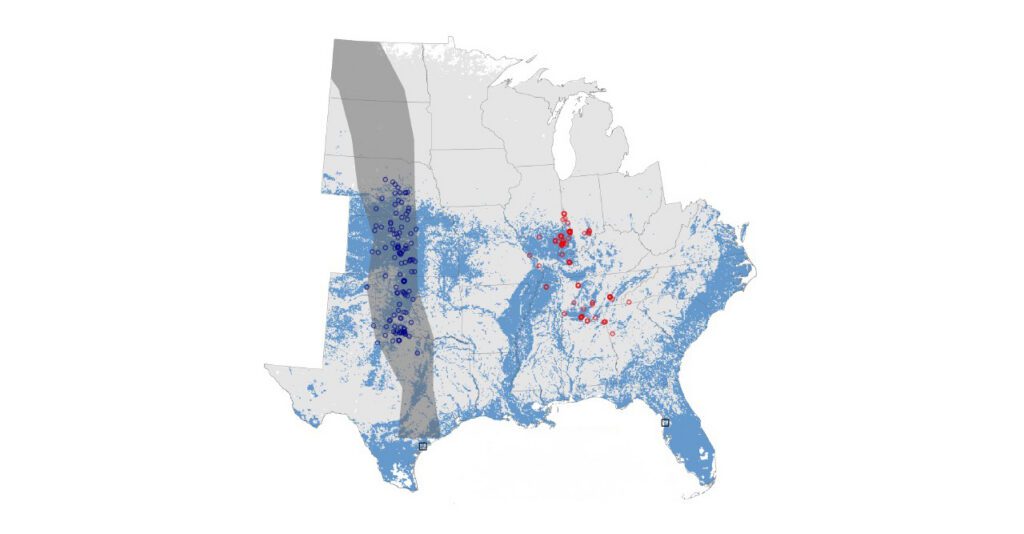

In 2025, researchers from the International Crane Foundation conducted a study looking at long-term nesting data in the Eastern Migratory Population collected over the last nineteen years. The goal was to better understand how renesting could be used to help cranes maximize breeding success, giving pairs more opportunities to raise chicks, within this reintroduced population. With natural occurrences of failed nests, the percentage of Whooping Cranes that renest is generally very low with only 38% of these birds renesting. This is not ideal as the population is not yet self-sufficient and maintains its numbers through the release of juvenile cranes raised in human care.

When parasitic black fly emergences coincide with Whooping Crane nesting season it can lead to high rates of nest abandonment as cranes are driven from their nests. At some sites where the rate of failed nests is high due to disturbance from black flies, a strategy known as forced renesting has been used to encourage breeding success. For forced renesting, both eggs are collected from Whooping Crane nests that are at high risk of disturbance from black flies. Cranes in this study whose eggs were collected as a part of forced renesting were more likely to lay another clutch of eggs than cranes who abandoned their nest. Therefore, forced renesting allows the maximization of the breeding season as, not only will the renesting Whooping Crane parents have the chance to raise a chick in the wild, but the two eggs collected will be incubated and raised in captivity to be released into the wild later that year.

A Whooping Crane tending to its nest with two eggs. Photo by Ted Thousand

There are several factors that play into the success of renesting, with one of the biggest factors being timing. Whooping Cranes whose nests fail early in the nesting season are most likely to renest, as opposed to Whooping Cranes whose nests fail later in the nesting season. This also means chicks from renests would hatch earlier, giving cranes more time to raise their chicks before they migrate south in the fall. Another important factor is the age of the birds nesting, particularly the age of the female parent. Older females tend to be more likely to renest when their nests fail compared to younger cranes. It is believed that older females have more experience nesting and may be more accomplished foragers, so they can maintain the resources they need to produce another clutch of eggs. One final factor is the habitat, Whooping Cranes who nest in wetlands other than the traditional sites they were released at tend to be more likely to renest if their nest fails. Future studies could examine reasons why this might be the case, including if the availability of nesting habitat or resources changes throughout the season differently at each site.

Based on the factors mentioned above and the cumulation of almost two decades of data, utilizing forced renesting for Whooping Crane nests at risk of nest abandonment due to black flies results in higher rates of renesting success than pairs whose nests fail naturally, so it is still an important management tool to help the population succeed.

It is important to understand the complexities of renesting and how a management tool like forced renesting may be beneficial in a reintroduced population that is not currently self-sustaining. Understanding renesting behavior and the factors that drive it allows organizations like the International Crane Foundation to maximize renesting success in these at-risk populations by targeting crane pairs for forced renesting that are most likely to succeed in a renesting attempt. Understanding what drives nesting success in Whooping Cranes is important to inform management decisions that support the continued success of this reintroduced population.

We thank Hillary Thompson, Andrew Caven, and Nicole Gordon the authors of the summarized manuscript “Renesting Propensity of Reintroduced Eastern Migratory Whooping Cranes” for permission to share their work.

References:

- Thompson, H. L., Caven, A. J., & Gordon, N. M. (2025). Renesting Propensity of Reintroduced Eastern Migratory Whooping Cranes. Wild, 2(2), 19.

Story submitted by Sam Urquidez, Outreach Biologist Assistant, International Crane Foundation