The water mud tugged at our legs as we walked through a small, freshwater pond, a lifeline for wildlife on the central Texas Coast, including the world’s rarest crane, the Whooping Crane. We are studying these critical oases and found they are extremely important to cranes during drought periods when the water in the coastal marshes becomes too saline to drink.

The Aransas-Wood Buffalo Population of Whooping Cranes spends nearly half their year in coastal habitat within and around the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Complex along the central Texas Coast. The population breeds at Wood Buffalo National Park in central Canada. During times of drought on their winter range, when bay salinities approach two-third strength of ocean water (exceed 23 parts per thousand), the cranes must seek new sources of fresh drinking water. As a result, they begin frequent daily trips to freshwater ponds in nearby upland prairie areas. These flights for freshwater take additional energy and may affect the cranes’ fitness for their long return flight to Canada in the spring.

What do parasites and salinity levels have in common?

We have studied these freshwater ponds since 2012, when Dr. Barry Hartup, our Director of Conservation Medicine, collaborated with other scientists from Texas A&M University. The team collected crane fecal samples between 2012 to 2014 to evaluate how two intestinal parasites may cause disease and potentially limit the growth of the crane population. In addition, we set up infrared game cameras to determine patterns of Whooping Crane use of the ponds and examined the site when the cranes were not present. The parasite study detected a high and persistent prevalence of coccidian parasites in the Whooping Cranes, although the degree to which parasites regulate the population remains unknown.

We continued this research by collaborating with Dr. Jeff Wozniak and his students from Sam Houston State University to monitor salinity levels in the salt marsh with established Whooping Crane territories and the effect of food availability from drought/wet cycles. In addition, the Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership, comprised of colleagues from the U.S. and Canada, had initiated an ambitious effort to capture wintering Whooping Cranes at the freshwater ponds and attach GPS telemetry devices for tracking the birds and color identification bands. Through this multi-year effort on the wintering and breeding grounds, the team marked 65 individuals, allowing us to identify birds at the freshwater ponds and in the salt marsh.

Creating new oases for the cranes

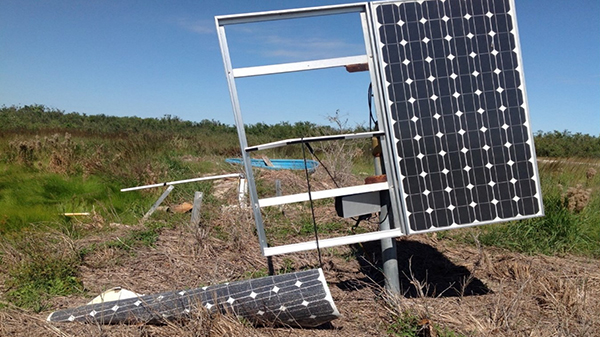

From the collaborative research results and our continued monitoring of how the cranes use the freshwater ponds, we found that each pond’s location on the landscape and the physical characteristics of the ponds are important to cranes. We also discovered that cranes tend to move the shortest distance from their coastal marsh territories to find drinking water. As a result of this research, we worked with the San Antonio Bay Partnership within the Water for Wildlife Project to drill a new well and install a solar panel at a shallow depressional wetland. The Whooping Cranes, as well as Sandhill Cranes, discovered the new freshwater source immediately, and our data showed that they were staying longer at the water source and feeding in the wetland margins.

We immediately began rethinking the installation of additional wells to provide fresh water and additional feeding habitat. However, the project took a different course with the direct landfall of Category 5 Hurricane Harvey in August 2017 within the Whooping Crane wintering range. Once we were able to access all the ponds with solar wells in early October 2017, we discovered all solar wells on the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Complex were damaged, as well as on one private ranch land.

Through a National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant, the Partnership repaired the wells and even added a few more on the landscape. We monitored 19 ponds on three peninsulas and one barrier island throughout the 2017-18 winter while the cranes were present. Interestingly, the pond use was active at many sites, despite the wet conditions following the hurricane. Once the cranes migrated, the Partnership worked with the Refuge to recontour the edges of several ponds to increase crane foraging areas.

Lessons learned

Our Texas Program work on crane use of wetland ponds continues to evolve, and, in our 11th year, we are establishing long-term monitoring sites on four of our private lands on two peninsulas. These sites have two objectives, to showcase the benefits freshwater ponds have on wintering Whooping Cranes and bring other coastal landowners and managers to the sites to discuss opportunities on their properties.

Through funding from the Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, we are developing a guidance document based on landowner experiences and our monitoring results to share with other landowners. In addition, we recently completed creating a new wetland pond where we can manage water levels and increase food availability for Whooping Cranes and wildlife. We hope to share this information and initiate conversations with new landowners who will have Whooping Cranes on their properties as the population expands.

Story submitted by Liz Smith, North America Programs Director, and Rari Marks, Leiden Conservation Whooping Crane Biologist. Click here to learn more about our work in North America.

Story submitted by Liz Smith, North America Programs Director, and Rari Marks, Leiden Conservation Whooping Crane Biologist. Click here to learn more about our work in North America.