The combined wild populations of two iconic Asian crane species – the Endangered Red-crowned Crane and Vulnerable White-naped Crane – are less than 10,000 birds. Because of the precarious situation of these wild populations, the world’s zoos have established conservation populations for both species. Within the European Association of Zoological Gardens and Aquaria (EAZA), both species fall into the Ex-situ Programme (EEP), formerly known as the European Endangered Species Programme, which establishes population management programs for selected species. One of the Program’s goals is to have a large enough captive population, if necessary, to return birds to the wild.

The North American counterpart is the Species Survival Plan, while Australian, Japanese and Indian zoos also have similar programs. Each EEP member has a coordinator and a species committee. The coordinator’s main task is to collect information on the status of all animals kept in European institutions, produce studbooks, carry out demographic and genetic analyses, produce a plan for the future management of the species and provide recommendations to participating institutions with the assistance of the species committee. An analogous program in the Russian Federation is the Protection of the Eurasian Crane driven by EARAZA.

Over 100 institutions in Europe currently have Red-crowned Cranes, with nearly 280 total individuals. These institutions have met established targets for Red-crowned Crane reproduction. The captive population is at its limits, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to find new institutions interested in breeding this charismatic species. The situation is similar for White-naped Cranes. The species is bred in 38 institutions involving about 90 individuals, and the targets for reproduction again have been met. The captive populations are therefore stable.

At the same time, our Russian colleagues’ results show that it is still possible to successfully release birds from captivity into the wild. Red-crowned Cranes were previously released in Japan, where a resident population is now stable, and in China. The Khingansky State Nature Reserve has been releasing cranes into the wild since 1988.

Transporting Eggs to the Far East

Brno Zoo officially entered the project in early 2014, and in 2015 we signed an agreement on egg transfer with the Khingansky State Nature Reserve. Egg transfer is always preceded by a marathon of complicated administrative and logistical processes, which are often further delayed due to the several-hour time lag between Central Europe and the Russian Far East. The preparation for the journey, which is especially demanding in terms of obtaining various permits, is complicated by the birds themselves. It is necessary to plan a fixed date only after the female begins to sit on the nest. The incubation date can vary among years by up to three weeks, depending on the season.

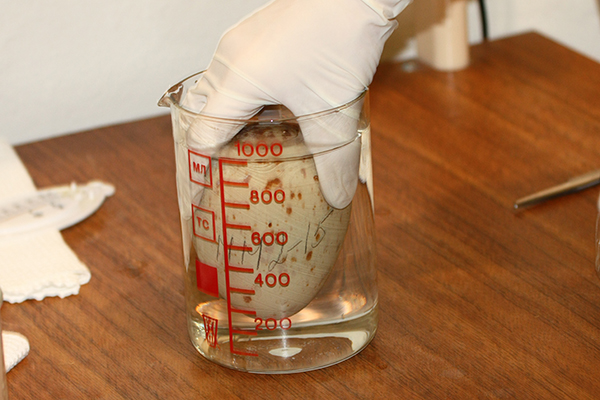

During incubation, it is advisable to check whether the eggs are fertilized. However, crane eggs have a very strong shell, so it is not often possible to determine whether there is an embryo in the egg by the classic method of illuminating it with light to see blood vessels. This is where a heart rate monitor comes in. The eggs are placed on a small rubber pad, which is connected to electronic measurement. An electrocardiography trace then appears on the display to indicate if the embryo’s heart is beating. More importantly, however, in the final incubation stage, the embryo’s gentle movements can be observed as it rotates in the egg. However, none of these methods is 100% reliable.

Editor’s note: Some research suggests that using a heart rate monitor may be prone to false positives and candling may be more accurate in determining an egg’s fertility. Researchers also are looking at determining fertility through spectrometry (identifying heat sources in the egg that correlate to an embryo), which may allow earlier identification of fertility. However, this process requires equipment and laboratory resources beyond what non-laboratory institutions would be able to accommodate.

While hatching chicken eggs can be transported when the embryo is not developing, crane eggs must be transported with an actively developing embryo inside, as its development begins immediately after fertilization and continues until hatching. Therefore, the eggs also have to be transported at the peak incubation stage, when the embryo is already larger and therefore more resistant to possible shock.

How Does Crane Egg Transfer Work? or “The Egg and I”

In mid-May 2015, the first transport incubator, containing two crane eggs, accompanied by an employee of the Brno Zoo, finally set out on a tiring journey across the Czech Republic to the Russian Far East, a journey of more than 10,000 kilometers lasting almost two days.

We originally planned to buy a travel incubator powered by electricity or a car battery and place it in the plane’s cargo hold. However, we were advised that this was not possible, so we had to find an alternative solution. Following the Russian methodology, we transported the eggs in a wooden box with walls insulated with polystyrene and heated by rubber bottles filled with warm water. During the long journey, the eggs needed to be under the constant supervision of a zoo employee, who had to check the incubator at approximately fifteen-minute intervals or add hot water to the thermal bottles. This meant two days without sleep! After the first somewhat difficult attempt, it was necessary to find a more effective method.

While specialists in both academic and commercial circles have extensive experience with the transport of biological samples stored at low temperatures, transport with heating, on the other hand, appears to be a methodical challenge. We managed to crack it only thanks to contacts with herpetologists from the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Brno. We made a new incubator of a polystyrene box in which a thermostat, a heating plate, a fan and a power bank were inserted, pictured above. As it is not possible to store the incubator on the floor of the aircraft deck (under the passenger seat) for safety reasons, it must be stored as hand luggage in the luggage compartment above the passenger seats.

In the Far East, Cranes Run by Train!

After a three-hour drive from Brno to Prague, there is a flight via Moscow to Khabarovsk, the “capital of the Far East.” In Khabarovsk, it is necessary to board a train with an incubator and then complete a journey along the Trans-Siberian Highway upstream of the Amur River. In Russia, the train is still one of the more reliable means of transport. The asphalt on the local roads is exposed to great temperature changes when frigid winters (around -30 °C) are succeeded by hot taiga summers (+ 40 °C). In such conditions, road expansion and contraction are extreme, making it far more difficult to maintain a smooth, pothole-free surface on roads.

The final destination, the town of Arkhara, lies directly on the highway itself. There, the Khingansky State Nature Reserve employees were already waiting for an employee of the Brno Zoo to take the eggs.

Are the Released Cranes Successful Colonizers?

Between 1991 and 2019, we returned a total of 104 Red-crowned Cranes and 61 White-naped Cranes to the wild. Some of the cranes flew to their wintering grounds, returned to their summering areas, and the happiest ones became parents of new generations of cranes in the wild. From the recovered data, we found that while the survival rate of White-naped Cranes is up to 43.5%, in the case of Red-crowned Cranes, this number is lower (24.5%). The reason for the difference is the different wintering grounds of each species. White-naped Cranes winter mainly in Japan, where there is a very strong community of birdwatchers. They actively provide their observations of the cranes with colored plastic rings. In contrast, this community is still nascent in China, and such data is collected only sporadically. The marked cranes thus move in the landscape without anyone noticing them. Despite the complications, however, it was possible to prove the nesting of released birds mated with wild birds – a great and indisputable success.

The Main Problems Solved in Cooperation

Among the difficulties with bureaucracy and logistics, which are often very exhaustive in international cooperation, veterinary concerns about the risk of introducing disease to the wild population can make it hard to obtain the required permits and prevent egg transportation. Between 2017 and 2020, the situation was strongly complicated by epidemiological waves of various diseases, including avian influenza, Newcastle disease and this year especially the coronavirus crisis. Despite these challenges, we continue to foster successful cooperation in the project.

The chicks from the Brno Zoo from the 2019 clutch could not be taken to the Far East as eggs due to logistical issues with the Moscow State Veterinary Administration, so we decided to take full-grown birds in February 2020. The transport was quite demanding due to the administrative and logistical challenges. Thanks to the transport company’s efforts and the Khingansky State Nature Reserve staff, it was finally possible to bring the birds to the reserve. They are currently acclimatizing at the reserve, and we expect them to be released next year.

In 2019, after an almost year-long bureaucratic process, two Red-crowned Cranes and one White-naped Crane were marked with our GSM tracking devices by the staff of Khingansky State Nature Reserve. These birds came from the related Oka State Nature Reserve in the Ryazan region of the Russian Federation. Read more about the journeys of two of these birds, White-naped Crane Arete and Red-crowned Crane Bomnak, pictured above. For now, we hope that our efforts will lead to acquiring more knowledge about these beautiful and interesting birds to promote their future conservation.

This project is co-financed by the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic.

Story submitted by Dr. Petr Suvorov, Curator of Birds at the Brno Zoo in the Czech Republic, with editing by Mikhail Parilov, MSc. and Irina Balan, MSc. of Khingansky State Nature Reserve in Russia.