In these times of working from home, social distancing and essential-only trips, we are increasingly appreciating what we usually have taken for granted – how connected we are to networks of people, be they friends, family or colleagues, and networks of places, whether that is the workplace, social venues or open spaces where we can enjoy nature.

For those of us working at the International Crane Foundation, not being able to conduct fieldwork, nor check in on how our cherished cranes are doing this spring, nor travel to our project sites, as far afield as Wisconsin, Zambia or China is a source of great frustration. But in a way, the lockdown has brought people together with a strong sense of purpose and connectedness.

For example, we have formed a Science Club, which gathers our staff together to discuss research. We are organizing a From the Field webinar series, which provides a platform for colleagues worldwide to share research, outreach, fieldwork findings and other crane and conservation information via Zoom webinars.

Colleagues are creating more journal articles about our research and fieldwork. And, colleagues are creating more outreach materials, like our Quarantine with Cranes blog series, which offers education and outreach for children of all ages.

Other groups are forming via Slack, our chat room app, around shared pastimes, such as a virtual running club, a crafting club, parenting group and zen-a-day. We also have a group that formed to sew masks for essential staff on our site. In addition, we are participating in virtual happy hours. This week’s virtual gathering features a pub quiz with prizes. And, we are having virtual birthday celebrations.

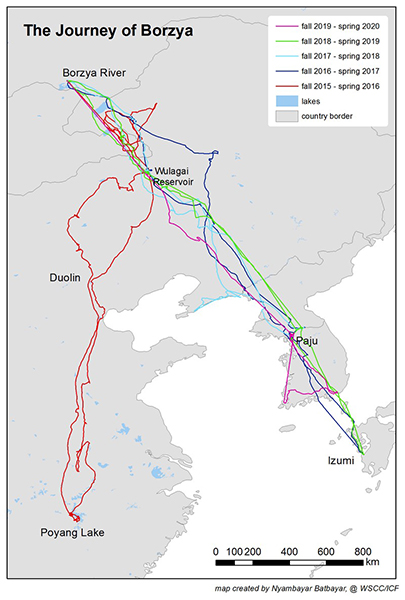

Personally, I have made and renewed contacts with colleagues in the field throughout East Asia, from Russia to Japan, as we try to use this time to put together stories of the journeys of our migratory cranes and the places they visit. These people normally are busy in the field now, banding and monitoring cranes, helping protect the places cranes depend on for breeding and migration. These colleagues are still busy, of course, and conveniently, satellite-tagged cranes can be followed from one’s home, a vicarious sharing of their migratory stopovers at welcoming wetlands.

In early March, I returned from a meeting of the signatory countries to the Convention on Migratory Species in Gujarat, India, and for the safety of myself and others, I went into immediate quarantine. The focus of the 130-country meeting was on “ecological connectivity,” broadly defined as “the unimpeded movement of species and the flow of natural processes that sustain life on Earth.” The intent was to integrate these concepts into the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (the “New Deal for Nature”) to be adopted under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in late 2020 in China.

The theme of the meeting was “Migratory Species Connect the World and Together We Welcome Them Home.” Indeed, all but one of East Asia’s eight crane species are long-distance migrants, dependent upon a critical network of sites along their flyways to complete their migratory journeys, including Demoiselle Cranes that migrate from China and Mongolia across the Himalayas to winter in Gujarat and nearby states in India.

But, while ecological connectivity underpins the successful conservation of migratory species, it needs human connectivity to sustain it. Connecting site managers, local communities and volunteers at key crane sites along the flyways is important to build shared awareness and appreciation of cranes and their journeys, knowing that only together can we fully protect them and the wetlands they depend on. Loss of just one or two key stopover or wintering sites can fatally interrupt their migration. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, after all.

One way we seek to build these connections is through linking schools and schoolteachers at important sites, such as between Keerqin in Inner Mongolia and Wucheng at Poyang Lake for Siberian Cranes in China, and between Ruoergai and Cao Hai for Black-necked Cranes on the Tibetan Plateau. Further afield we have held international “crane camps” in Russia, China and Korea.

Crane migration also connects our colleagues and researchers across flyways as they follow tracked cranes. See The Journey of Borzya the White-naped Crane for a recent example. Which brings me back to the heightened sense of human connectivity.

In our current state of lockdown, we have an opportunity to link to each other within and across countries and to raise the awareness and visibility of the connections among cranes, wetlands and people. I hope this can become a lasting legacy of this difficult time and we can remember it as one day, hopefully soon, we return to our offices, travel and fieldwork.

Story submitted by Spike Millington, Vice President International – Asia. Click here to learn more about our work in East Asia.

Story submitted by Spike Millington, Vice President International – Asia. Click here to learn more about our work in East Asia.