The wintering range of the Aransas-Wood Buffalo population of Endangered Whooping Cranes maintains a delicate balance in an area subject to serious environmental changes and degradation. Currently, the Port of Corpus Christi ranks 6th for annual tonnage in the nation and expansion plans threaten the integrity and productivity of the wintering range. Read below the International Crane Foundation statement in opposition to proposed changes to the Corpus Christi Ship Channel and alternatives proposed to minimize environmental damage.

Three major activities are being pursued in and around Harbor Island and Port Aransas, Texas, that raise the specter of harm in violation of Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. These activities also jeopardize the continued viability of the Aransas Wood Buffalo wild Whooping Crane population in violation of Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act. They pose a direct risk to the cranes. We oppose these activities as proposed and ask your assistance in ensuring they are abandoned or restructured to eliminate the potential of harm to these wonderful, endangered birds.

In the following paragraphs, we describe the usage pattern of Whooping Cranes near the Harbor Island area. We also describe these projects that are generating concern and the reasons why they should be abandoned or modified.

Whooping Cranes Winter Near Harbor Island

The Whooping Crane flock is growing and expanding beyond traditional territories within or even near Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The birds are moving northward into the Matagorda Bay system, westward along Copano Bay and south down San Jose Island, and across the Corpus Christi Ship Channel to Mustang Island on the backside of Port Aransas. As can be seen from Figure 1, these birds are close to the Corpus Christi Ship Channel, an important fact that is discussed in later sections.

The annual surveys conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service do not include Mustang and Harbor Islands. Therefore, the continued presence of Whooping Cranes in this area is not documented. The International Crane Foundation initiated a Citizen Science Project last February to March 2019, using a video monitoring approach and continued the study this winter season between November 2019 to March 2020. The objective of the study includes documenting crane presence when visible on northern Mustang Island and evaluating habitat quality using crane behavior, such as foraging and resting. The study will compare this site to areas cranes use in the established wintering habitat sites within Aransas National Wildlife Refuge.

Our preliminary results indicate consistent use of Mustang Island habitat by a pair of Whooping Cranes in late February to March 2019, with nine days covered over a 23-day period. Citizen scientists recorded 322 minutes of video and 16, 20-minute videos for analysis. The study continued from November 2019 to March 2020, documenting one pair and a single Whooping Crane, with 58 days covered over an 89-day period. 2,636 minutes of video, including 90, 20-minute videos will be used to evaluate crane use of habitat.

This project has been accepted as the focus of a Master’s thesis project to characterize how Whooping Cranes use the habitats on northern Mustang Island with other sites within the traditional wintering range. It is expected that the findings will provide the scientific evidence of the importance of this area to the expansion of the Whooping Crane wintering range.

The Projects of Concern

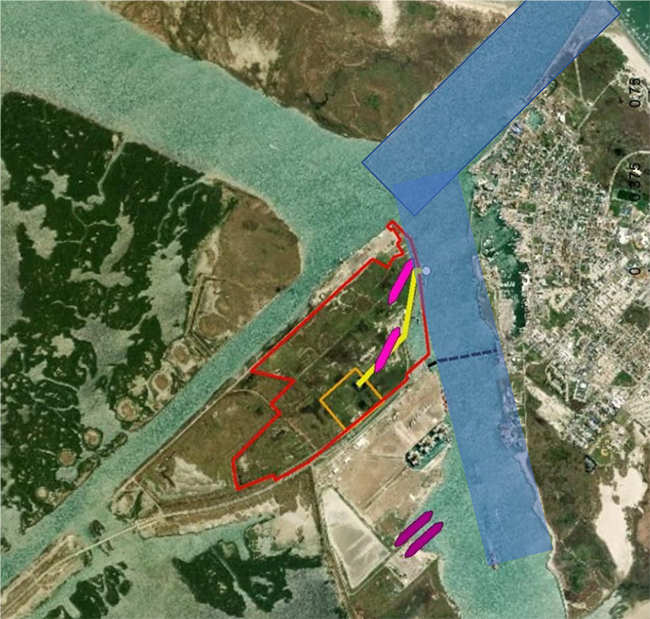

Three major new activities are proposed in the immediate vicinity of the Whooping Cranes shown above. First, the Port of Corpus Christi is proposing to deepen the Corpus Christi Ship Channel from about 50 feet to about 80 feet. This will allow supertankers to come in through the jetties at Port Aransas to Harbor Island. Additionally, two major terminal development projects have been proposed on Harbor Island that would serve these supertankers and load them with oil to be exported to overseas markets. Further, there is a desalination plant proposed for Harbor Island that would discharge its reject brine directly into the ship channel. Together, these three projects represent a bona fide threat to the wintering Whooping Cranes. The locations of the three proposed projects are shown in Figure 2.

The problems here are many. They involve a risk of direct harm to the Whooping Cranes using Port Aransas and San Jose Island and indirect harm due to potential negative impact to blue crabs, the major food source of the Whooping Crane flock. We believe these risks raise the potential of jeopardy to the cranes under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, as discussed below. These risks likely will result in harm to the wild flock in violation of Section 9 of the Act.

A. The Proposed Deepening of the Channel and Berths for Supertankers on Harbor Island

The potential deepening of the ship channel will allow larger crude carriers to come in through the pass and load on Harbor Island. Here, the key issue is the risk of an oil spill from a collision between a tanker maneuvering full of crude and other increased traffic. Not only is this the Corpus Christi Ship Channel, but it is also the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which continues north along the San Jose shoreline into Aransas Bay and points north. The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway has significant tug and barge traffic with petrochemicals and aggregate, and the ferry crossing is right in the middle of this situation. If such a spill were to occur during the wintering season, multiple birds would be in the pathway of harm. The oil would move with the tide, which is very strong coming in through the jetties and would disperse the oil northward as well as onto the marshland behind Port Aransas where the cranes in Figure 1 winter.

There is no doubt that the risk of an oil spill will be greatly increased by bringing supertankers into Harbor Island. Common sense tells us that. Common sense also suggests that if there are viable alternatives that do not raise such risks, they should be pursued. And as is discussed in Section C below, such alternatives exist.

B. The Impact of Brine Discharge into the Pass Between Mustang and St. Joseph’s Islands

Second, consider the impact of the discharge of brine material into the channel adjacent to the pass into the Gulf of Mexico. This brine is “reject water” from the desalination process that is proposed to be constructed on Harbor Island. The International Crane Foundation is not opposed to the desalination facility, but to the location of the discharge. Brine concentrations reported in the literature vary from 50 to 75 g/L. The brine discharge has a much higher density than seawater and therefore tends to fall on the seafloor near the brine outfall outlet (plume effect), creating a very salty layer that can have negative impacts on the flora and the marine life and any related human activities. This level of brine salinity is toxic to juvenile marine life, such as blue crabs.

Blue crabs are the principal food for the wintering Whooping Cranes. Blue crabs migrate into the Gulf to lay their eggs, and their larvae come back into the bay to mature. In their early stages, these larvae are planktonic and must depend upon the tide to move them into the bay. When the tide goes out, they will migrate vertically in the water column and drop to the floor of the channel and secure themselves until the tide reverses. The more advanced larval stage – the megalops – tend to stay near the bottom. In this way, these larval blue crabs will enter the toxic mixing zone, and the food supply of the cranes, and therefore the cranes, will be harmed. As this discharge will be continuing, essentially a kill zone will be created to the detriment of larval blue crab and other migrants that are planktonic or stay near the bottom.

There is no question of the risk of this concentrated brine discharge to these larval crabs. Once concentrations exceed the seawater, the survival rate declines precipitously in most marine organisms. Larval forms are particularly sensitive, and most of the crabs found in the lower portion of the Whooping Crane habitat are tied to the pass at Port Aransas. By killing these larval crabs, this discharge poses a direct threat to the survival of the Whooping Cranes using the habitat adjacent to Aransas Bay as well as Copano, St. Charles and Mesquite Bays.

C. Potential Solutions

Solutions exist for each of these problems. First, the brine discharge can be routed out several miles into the Gulf, away from the fish pass. Here, the mixing zone issue is much less focused than it is in the pass, which is the corridor for all marine organisms moving to and from the bay. Second, an alternative exists to the deep channel in the form of an offshore monobuoy terminal. Such monobuoys have been operated safely around the world and would provide the least damaging alternative to the destruction and risk associated with dredging a deeper channel and building terminals onshore. Given the current economic situation, the need for multiple export facilities is highly unlikely. By pursing the least damaging alternative, the potential harm of the deep channel generally and specifically to the Whooping Cranes is significantly reduced.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the International Crane Foundation expresses its opposition to the deepening of the Corpus Christi Ship Channel, is opposed to the two terminal projects and is opposed to the discharge of brine into the Corpus Christi Ship Channel. There is no need to risk jeopardy to the cranes in violation of Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act or the possibility of a take in violation of Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. Excellent alternatives are available that would avoid jeopardy and harm and still create economic benefits.