In the spring of 1985, I was awarded the Gold Medal from the World Wildlife Fund at an annual meeting of their Board of Directors in Geneva, Switzerland. Prior to that gathering, I had camped under the open skies near the Okavango Delta in Botswana, where I contracted malaria, a disease that did not manifest itself until a few weeks later in Russia, where I delivered some Siberian Crane eggs to the Crane Breeding Center at the Oka State Nature Reserve. Thinking it was just the flu, I pushed on with a good day, followed by a day with a high fever. On my way home to Wisconsin, I planned to stop briefly in Geneva for the World Wildlife Fund meeting, hoping that my health would hold for the ceremony.

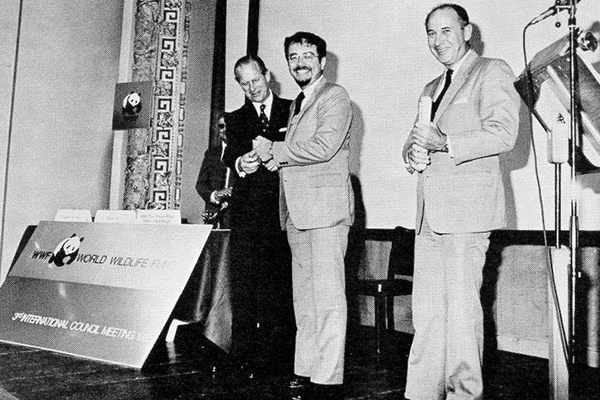

Fortunately, the day in Geneva was an exceptionally good day. Another recipient of honor and a great friend of mine, Canadian wildlife artist Robert Bateman, and his wife Birgit and I stayed together at a small hotel just across the border in France. Weary from travel, we rested in the morning, received our honors presented by Prince Philip in the afternoon, and attended a banquet at a hotel with a view over Geneva that evening. Everything went smoothly until our arrival at the reception on a wide balcony preceding the dinner.

The World Wildlife Fund International Gold Medal was presented to George “in recognition of his unique contribution to the survival of the world’s cranes and the conservation of their wetland habitats, through the International Crane Foundation and his contacts with scientists in many countries, especially China, India, Japan, Korea, Thailand and the USSR.”

Although I wore a suit and looked presentable, I was unprepared for the formal glitter of the occasion and felt uncomfortable fearing that my illness might return. So, I kept apart from the crowd until I noticed another man doing the same. Deciding to introduce myself, I discovered he was from Nepal, a member of the World Wildlife Fund Board, and wanted to know all about cranes. I poured forth. Aware of the one-sided nature of the conversation, I inquired about his profession and was astounded, then embarrassed, when he calmly announced that he was the brother of the King of Nepal. Gulp!

When people headed for the dining room, I decided to be the last one in. I wanted to find a place near the door in case I became ill and needed to escape. Entering after all were seated, I timidly looked around for a seat among even more sparkle. Far away and beside huge windows looking out over the city, the head table hosted Prince Philip, Luc Hoffmann (a co-founder of World Wildlife Fund), Bob and Birgit Bateman, His Highness the Aga Khan and his wife, and a wealthy lady from Brazil who hosted the dinner and sat beside Prince Philip. The chair between the Prince and Mrs. Khan was unoccupied.

Prince Philip spotted me, stood up, and started beckoning me to join him. So, there I was, for a meal that lasted several hours, seated between royals, both of whom proved to be gracious, warm, and delightful. Prince Philip told me that although devoted to conservation, he initially wondered that as a hunter, he might not be appropriate as the patron of the World Wildlife Fund. We shared stories of experiences with wildlife. During the 1970s, I studied cranes for one winter in Iran during the reign of the Shah, who was close to the Aga Khan. Mrs. Khan wanted to know about my adventures catching and banding cranes at wetlands in the Alborz mountains near Iraq.

The following day I spiked a high fever on the flight back to the U.S. After a week of progressive weakness, I was hospitalized in isolation. Eventually, with the disease revealed and treatment administered, my health rapidly returned, and I have never had a recurrence. The passing of Prince Philip brings back that special day when we shared a celebration and a meal that the Prince mildly complained took much too long to deliver and which he revealed, with a smile, was a custom of the gracious Swiss.

Story submitted by George Archibald, Co-founder and Senior Conservationist.

Story submitted by George Archibald, Co-founder and Senior Conservationist.