Stories of the wonder of cranes have been told and shared for thousands of years – not surprising considering cranes are among the oldest family of birds alive today.

“Their mystery and wonder drive us to find out more so that we can ensure our efforts to conserve them are fitting and effective,” says Tanya Smith, South Africa regional manager of the Africa Crane Conservation Program, a partnership program of the Endangered Wildlife Trust and International Crane Foundation. “With 11 of the world’s 15 species of cranes threatened with extinction, it’s sad to admit that all four of Africa’s resident cranes are on that list. We have our work cut out to halt the declines we bear witness to.”

South Africa is home to three of Africa’s four resident cranes, namely the Blue Crane (our national bird), Grey Crowned and Wattled Cranes. In Africa, the endangered Grey Crowned Cranes are showing the fastest decline. South Africa, however, has the only confirmed increasing population of the endangered Grey Crowned Crane. And, our Wattled Cranes also are showing consistent growth over the past two decades, with 380 Wattled Cranes counted during the 2018 aerial crane surveys.

“This is an incredible achievement that serves as inspiration for efforts in the rest of Africa to conserve cranes,” continues Smith.

With the advent of satellite tracking and the advancement of technology, conservationists can delve deeper than ever before into the lives and biology of a species.

“For the first time in the world, we have successfully fitted satellite trackers to five wild Wattled Cranes, thanks to the collaboration between the Endangered Wildlife Trust/International Crane Foundation partnership, the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the KwaZulu-Natal Crane Foundation and Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife.”

Valuable information collected through satellite tracking

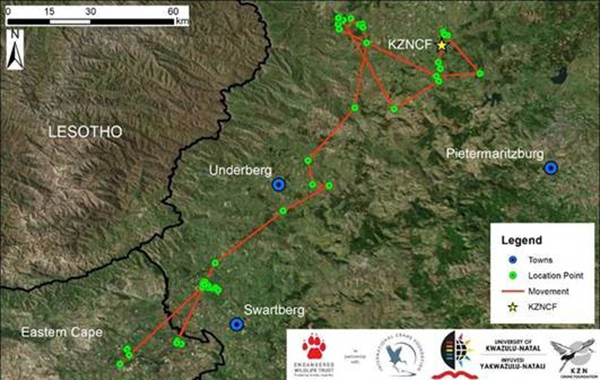

Although non-migratory in the true sense, Wattled Cranes in South Africa tend to form “non-breeding” floater flocks that move across the eastern grasslands of the country. Results from the trackers have demonstrated a seasonal movement of the non-breeding portion of the population between the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands and the Southern Drakensberg region near Cedarville.

“These birds, often as young as one-year-old, make a direct overnight flight of over 200 km, where they then spend several months over summer and autumn in the floodplains of the Umzimvubu River, otherwise known as the Cedarville flats, before returning to the KwaZulu-Natal midlands at the start of winter.

This valuable information allows us to focus conservation efforts in both breeding and non-breeding range of Wattled Cranes – unfortunately still listed as critically endangered in this country – to ensure safe spaces for cranes through collaborative partnerships,” says Smith.

Cranes released into the wild after being painstakingly reared by humans

Understanding the movements of Wattled Cranes in the wild in South Africa has come at an important time. Two young Wattled Cranes reared by humans dressed in crane-costumes have now been released in floater flocks by the KwaZulu-Natal Crane Foundation.

As part of the Wattled Crane Conservation and Research Programme, the KwaZulu-Natal Crane Foundation undertook the ambitious task of rearing Wattled Cranes chicks hatched from second eggs collected from the wild. “Second eggs are abandoned by the parent birds once the first egg hatches,” explains Smith.

The first two birds were successfully raised at the isolation rearing facility in Nottingham Road, KwaZulu-Natal and the birds, affectionately known as Isabelo and Umfula, have been released into two different flocks of non-breeding Wattled Cranes.

“Fitted with satellite trackers the research team are able to monitor their movements in relation to the wild birds and document their integration into the wild. This is an exciting stage for the conservation of Wattled Cranes, where several partners have worked tirelessly for the past two decades to halt the decline of a species that was perilously close to extinction. We are able to now spend valuable time and resources in getting answers to so many questions that have been left unanswered,” continues Smith.

Why are Crane conservationists dressed so peculiarly?

When hand-rearing crane chicks, human caretakers are required to dress in special crane costumes and to mimic the behaviors of adult cranes to teach the youngsters the skills they will need to survive in the wild.

Costume-rearing is a proven and effective technique to avoid “humanization” of the birds. By following this technique, crane chicks stand a better chance to successfully be released back into nature.

For the first two weeks, costumed parents spend the nights with their chicks as they require to be fed every two hours. Caretakers also take their crane chicks for regular walks and teach them how to forage and feed on foods in their natural wetland habitats.

Rearing cranes in captivity is a slow and fascinating process, requiring absolute commitment, but every chick successfully raised and released is a gift to our heritage.

Special habitats and species are receiving special protection in KwaZulu Natal

“Together with farmers, other conservation organizations and non-governmental organizations, the South African government, state-owned enterprises such as Eskom and funding partners, we have worked for over two decades to reverse the decline of all three of South Africa’s cranes and protect the wetlands and grasslands that are the backbone of our natural heritage.

We focus on protecting private and communal land through a voluntary, but a legally contractual process called the Biodiversity Stewardship Programme. Within KwaZulu-Natal – thanks to our ingenious legislation, civil society and government – various partners together have been able to declare 32 private and communal Nature Reserves and nine Protected Environments. These areas are protecting special species such as our cranes, chameleons, blue swallows, oribi antelope, golden moles and so much more.

Together with landowners, we work to a future where land is managed sustainably, wetlands and grasslands support biodiversity while supplying us with essential life services such as clean water, provision of water during dry seasons, carbon sequestration, natural materials for houses and crafts, as well as grazing for livestock.

Thanks to all our partners for making a difference,” concludes Smith.

Story submitted by Tanya Smith, South African Regional Manager. Click here to learn more about our work in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Story submitted by Tanya Smith, South African Regional Manager. Click here to learn more about our work in Sub-Saharan Africa.