Travels with George: Following the Siberian Crane migration in Yakutia, Russia

One of the greatest joys of my life with cranes is friendship with others who share such passion for these special birds. My colleagues at the Institute for Biological Problems of the Cryolithozone (permafrost) – IBPC in Yakutia, Russia, Drs. Nikolai Germoganov, Inga Bysykatova and Masha Vladimirtseva have been such friends for many years.

Siberian CraneThrough Siberian Cranes, Masha has become close to fellow Craniacs Rosa and Alexi Zelepukhin. The couple lives beside a tiny meteorological station on the West Bank of the Aldan River just across from Okhotsky Perevoz village in Yakutia. Now retired, Alexi was an electrician and Rosa was the former director of the meteorological station. Two of their four sons became game rangers. Tragedy struck when one was killed by poachers in 2002.

From about 1717 through 1862, Okhotsky Perevoz had a population of about 3,000. Goods traveled by boat from the capital of Yakutia, Yakutsk, to Okhotsky Perevoz, and then about 600 miles overland to the coastal seaport, Okhotsky. After roads and rails connected Yakutsk to the world, the trail was abandoned and the population of Okhotsky Perevoz declined. Today there are 138 residents.

In 1962, at age 17, when Rosa first lived near the village, she noticed that each spring and autumn flocks of Siberian Cranes flew over their home. She started to keep records of their numbers. Later she met professional ornithologists visiting from IBPC and was amazed to discover the cranes were endangered and that their migration corridor was narrow. She viewed the cranes through new eyes and enlisted the involvement of others in organized surveys. They discovered the counts in autumn were much higher than in spring and that the majority of the flocks flew over their village in late September and early October. An autumn count at Okhotsky Perevoz is perhaps the easiest way to monitor the size of the East Asia population.

To thank Rosa and Alexi for their dedication, in early October 2018, a member of the International Crane Foundation Board of Directors, Jennifer, and I was able to join Masha, Nikolai and two other colleagues from IBPC for Nikolai’s first visit to Okhotsky Perevoz. Getting there from Yakutsk was no easy task. It took two days. The first day included a wait for a ferry across the Lena River, a five-hour drive over a dusty bumpy road, a wait for a ferry across the Aldan River and an overnight stay. The second day was a cold, windy three-hour upstream journey in two small four-seater motorboats.

Upon arrival, Rosa and Alexi were busy in their small, rustic winter home preparing a meal that included homemade bread, fried fish and a soup of beef, onions, cabbage and potatoes. Jennifer, Masha and I were allocated to sleep in their more spacious summer house nearer the river. A generator provided electricity and the buildings are heated by thick ceramic traditional stoves in which wood fires provide warmth, an oven for baking and a surface for cooking. They lacked a well and water is carried from the Aldan up the hill to the dwellings. The warmth of their rustic kitchen was matched by the cordiality of this remarkable couple who had overcome tragedy and inconveniences.

After the long journey and a hearty evening meal, I retired for a long rest in a cozy bed with great anticipation of counting Siberian Cranes the following day despite the doubts of Nikolai. He predicted it would take a blast of winter to push the cranes from their staging areas on the tundra, about 310 miles over mountains to meet the Aldan at Okhotsky Perevoz and then south towards China. We had only the next two days to watch for cranes. Would they appear?

October 2, 2018

It’s 4:30 a.m. and I’m wide awake and brimming with anticipation of the sound and sights of Siberian Cranes in the sky. I dress and tiptoe from the summer house not wanting to disturb the slumber of Jennifer and Masha.

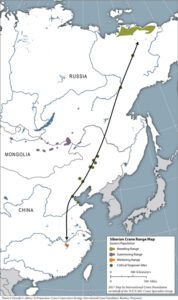

The first light on the eastern horizon is punctuated by 14 bright street lights along the single, long earthen road that links the homes in Okhotsky Perevoz across the river. The Aldan flows north to join the Lena River that eventually crosses the tundra and dumps into the Arctic Ocean. About 845 miles east of the mouth of the Lena is the mouth of the Kolyma River. The 503-mile wide band of tundra between these rivers is the breeding area in summer of the critically endangered Siberian Crane.

As I walked for an hour in the moonlight along the gravel shoreline of the Aldan across from the village, the silence was broken only by a few moos from a cow, followed a half hour later by a chorus of barking as dogs greeted the new day. A few crows and a raven called, and a lone wild goose honking as it flew south along the north-flowing river. There was not a breath of wind then, nor during that entire day. The silence was a gift.

At 7:30 a.m. I returned to Rosa and Alexi’s winter home for a hearty breakfast of potato and fish soup, rice porridge, boiled eggs and fresh homemade bread with butter and jam. Then Jennifer, Masha and I walked north along the riverbank and through fields punctuated by scattered deposits of fresh horse manure and stacks of hay surrounded by birch rail fences. Eventually, we reached a spot with a commanding view in all directions. This was Masha’s favorite spot for counting Siberian Cranes.

Facing the east and seated on the grassy bank, we waited through more silence broken only by a small flock of redpolls, a sparrow-sized bird of the Arctic. At 8:55 a.m. a flock of about 20 unidentified ducks flew low up the river. Then at 9:45 from the north we were thrilled to hear faint flute-like calls of Siberian Cranes. We jumped to our feet and with binoculars searched the clear blue morning sky. Initially, we looked too low. Masha found them. Pointing upward and to the west, she cried, “Look up!” Twenty-eight sets of glistening white wings tipped in black cut with rapid beats into the still, cold air before they vanished beyond the forest of white birch. We were without words!

We remained at our post until mid-afternoon. Colleagues upstream spotted 14 more cranes coming from the east, and later we learned that 12 more had been sighted by villagers on the east side of the river. But that was it for cranes.

In late morning a motorboat carrying three teachers and two students arrived to join us to look for the cranes. They traveled about 100 km upstream from another village, a more sizeable community with 70 students and 20 teachers.

Their leader was a teacher of Russian literature and a “Craniac.” Last year she spent four days, obviously the wrong ones, at Okhotsky Perevoz and only saw two Siberian Cranes. She secured from Masha the sighting data from autumn 2017 and gave it to one of her students, who in turn produced such an excellent report about Siberian Cranes that he won a contest. So here she was again, this time with two other teachers, the winning student and one of his buddies. They could only stay for three “craneless” hours and then headed home. But we got to know each other, and I’m looking forward to the growth of that friendship. I feel in my bones she can be of enormous help to Rosa and Masha in the future.

The highlight of the glistening white flute-calling apparitions in the sky was almost overshadowed by a visit to the school in Okhotsky Perevoz that evening. Whereas many of the buildings in the village are in ruins or on that path, the school was new, setback in the forest, spacious and immaculately clean and staffed by a principal, a cook and four teachers that served 11 students in grades one through nine. Masha had created baseball hats with cranes for the boys and white cloth bags with cranes — all designed by Masha–for the girls. I gave the English teacher my book, “My Life with Cranes,” and the students a bunch of colorful origami cranes and a memory card game about cranes created by a friend in Germany. Everyone was so excited. It was like Crane Christmas morning! Then with everyone gathered around, I showed dramatic videos of various crane species doing interesting things while Masha translated vigorously. Our party ended with treats from Sergei, the cook, in the dining room with all the girls, boys and teachers at separate tables. The guests joined the teachers for crepes topped by cream with fresh crane berries and jam.

The teachers told me that children go to a downstream town for high school and then they are grown. They go off for employment elsewhere and the village continues to shrink.

October 3, 2018

On this date last year hundreds of Siberian Cranes poured over Okhotsky Perevoz. But this year the unseasonably warm weather must have slowed the migration. Not a crane appeared. At 10:42 a.m. a mixed gaggle of Bean and White-fronted Geese flew over Rosa and Alexi’s property and vanished to the southwest, the typical flight path of most geese and cranes. It was overcast and chilly so we made a fire in the field above the river and waited until 1 p.m.

Although the Siberian Crane nesting area in Russia is vast, their major wintering area is a single spot on the map, Poyang Lake in China, about 3,000 miles to the south. Midway along the narrow migration route, the cranes rest and refuel at a wetland in northern China called Momoge. Although key portions of both Poyang Lake and Momoge wetlands are protected as nature reserves, these wetlands so vital to the cranes, are sensitive to human-induced changes in water flow both inside and outside the protected areas. The fate of the Siberian Cranes, therefore, rests mainly in China, although changes in the breeding area from warmer summers and melting permafrost also affect the cranes.

I was sad to bid farewell to our gracious hosts. I promised to return and spend two weeks to participate in a thorough 2019 count. A few days later, Rosa called Masha to report that more than 1,000 Siberian Cranes had flown over her home!

Story submitted by George Archibald, Co-founder and Senior Conservationist. Click here to learn more about our work in East Asia.