From Egg to Fledge: Understanding Whooping Crane Chick Survival

Reintroduced in 2001, the Eastern Migratory Population (EMP) is one of two migratory populations of the Endangered Whooping Crane. Unlike the historic Aransas-Wood Buffalo Population (AWBP), the EMP is not yet self-sustaining, which means it is not able to grow without human intervention. In the EMP, recruitment does not exceed mortality; in other words, not enough wild-hatched birds survive into adulthood to offset losses in the population. As a result, the EMP relies on the continued release of captive-reared birds into the wild and targeted management to sustain its population.

Previous research, coupled with ongoing habitat and nest management, has helped improve nest success in the EMP over the years, but chick survival remains low. Between 2006 and 2023, only about 18% of wild-hatched chicks in the EMP survived to fledge, which is the point at which juveniles have flight feathers and are strong enough to fly. The greatest risk of chick mortality is during the first three weeks after hatching, but mortality risk is much lower once the chicks fledge. While fledging rates have improved in this population since 2010, they still lag about 20% behind those of the self-sustaining AWBP.

So, how can we ensure that more chicks in this population survive to adulthood? First, we need to understand better what factors influence chick survival in the wild. Our team recently led a study to do just that, monitoring chicks hatched between 2006 and 2023 throughout Wisconsin. The results of this study will inform future management strategies aimed at increasing chick survival and supporting population growth in the EMP.

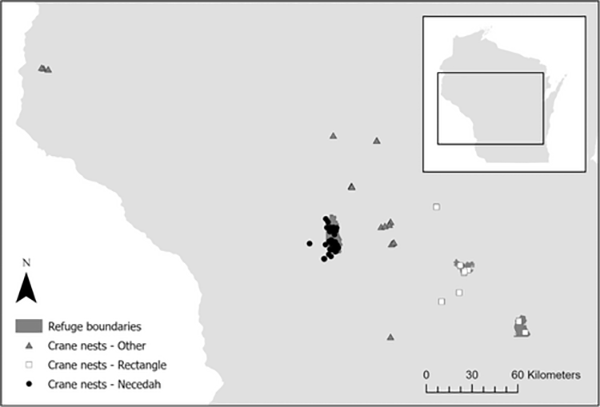

Figure 1: Map of successful Whooping Crane nests in Wisconsin from 2006-2023.

This study examined factors that may influence Whooping Crane chick survival, including nest and chick characteristics, parental experience and rearing history, habitat and region, and weather and climate. Nest and chick characteristics included the number of eggs on a nest, whether the nest was the first, second, or third attempt of each pair every year, and the hatch date of each chick. Parental experience referred to the age and years of nesting experience of parent cranes, whereas parental rearing history detailed whether parents were wild-hatched or captive-reared. Finally, researchers gathered data on nest location, habitat, climate, and weather, such as precipitation or temperature, to explore their effects on chick survival.

A series of models predicted that Whooping Crane chicks without a sibling had a higher likelihood of survival than those with siblings. Current management in the EMP calls for the removal of one egg from two-egg nests to provide eggs for captive rearing and release into reintroduced populations like the EMP. Since this management action likely also improves chick survival, this practice should continue.

A series of models in the study predicted that Whooping Crane chicks without a sibling had a higher likelihood of survival than those with siblings. Photo by Bev Paulan

In addition, warm weather, defined as days over 32°C (about 90°F), was associated with greater chick survival, particularly early in the chick-rearing period. Warmer weather may promote chick survival by increasing food availability or reducing the amount of time parents must spend brooding to regulate chicks’ body temperatures, thereby increasing the time they can spend foraging for their chicks.

Finally, this study revealed that greater parental experience may be a key factor in chick survival and recruitment. Recruitment rates have been slowly increasing as the population ages and individuals gain nesting experience. However, these rates would increase more quickly if adult cranes survived longer in the wild. Some of the greatest threats to adult Whooping Cranes include powerline collisions, predation, and poaching. Given this study’s finding that parental experience impacts chick survival, our management plan will continue to address both adult and chick survival in tandem.

This study further revealed that greater parental experience may be a key factor in chick survival and recruitment. Photo by Tran Triet/International Crane Foundation

The results of this study revealed several factors that influence Whooping Crane chick survival in the wild, which help us understand how to better manage this population in the future. Our team will continue to explore other factors affecting survival and population growth, including risks or threats faced by both juvenile and adult cranes. For example, although landscape-level habitat had no significant impact on chick survival in this study, smaller-scale habitat on the breeding grounds could affect predation risk. Therefore, we are developing a study to assess how habitat management, such as woody vegetation removal, can increase visibility of predators and reduce risk for Whooping Cranes. By identifying and better understanding these risks or threats, we hope to inform management of the population and its habitat so the EMP can ultimately reach self-sustainability.

We thank Hillary Thompson, Andrew Caven, Stephanie M. Schmidt, Bianca Sicich, Alexis Sarrol, Eva Szyzykoski, and Nicole Gordon, the authors of the summarized manuscript “Whooping Crane Chick Survival in the Reintroduced Eastern Migratory Population,” for permission to share their work.

Story submitted by Olivia Burkholz, Outreach Program Assistant, and Stephanie M. Schmidt, Lead Outreach Biologist, International Crane Foundation.

Top photo by Tom Lynn

July 16, 2025