Are We There Yet? Differences in Migration Behavior Between Whooping Crane Populations

A juvenile Whooping Crane flies alongside two adults in Indiana. Photo by Dan Kaiser

The two populations of North America’s migrating Whooping Cranes exhibit vastly different behaviors on their journey south. The remnant Aransas-Wood Buffalo Population (AWBP) migrates about 2,500 miles along the Central Flyway to reach their historic wintering grounds in coastal Texas. The Eastern Migratory Population (EMP), a reintroduced population established in 2001, was originally taught to fly to coastal Florida to salt marshes that mimic the conditions of the wintering habitat in Texas. This migration corridor is known as the Eastern Flyway. Since reintroduction, the wintering territory of EMP Whooping Cranes has shifted northward, in some cases nearly halving the total migration distance, a behavior known as shortstopping. Today, EMP birds primarily winter in southern Indiana and northern Alabama. Understanding what drives shortstopping in Whooping Cranes is important. Birds that overwinter closer to their breeding grounds expend less energy during migration, but expanding into new spaces can be risky and may indicate a decline in available habitat.

A juvenile Whooping Crane in the remnant population forages with its parents at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Ciming Mei

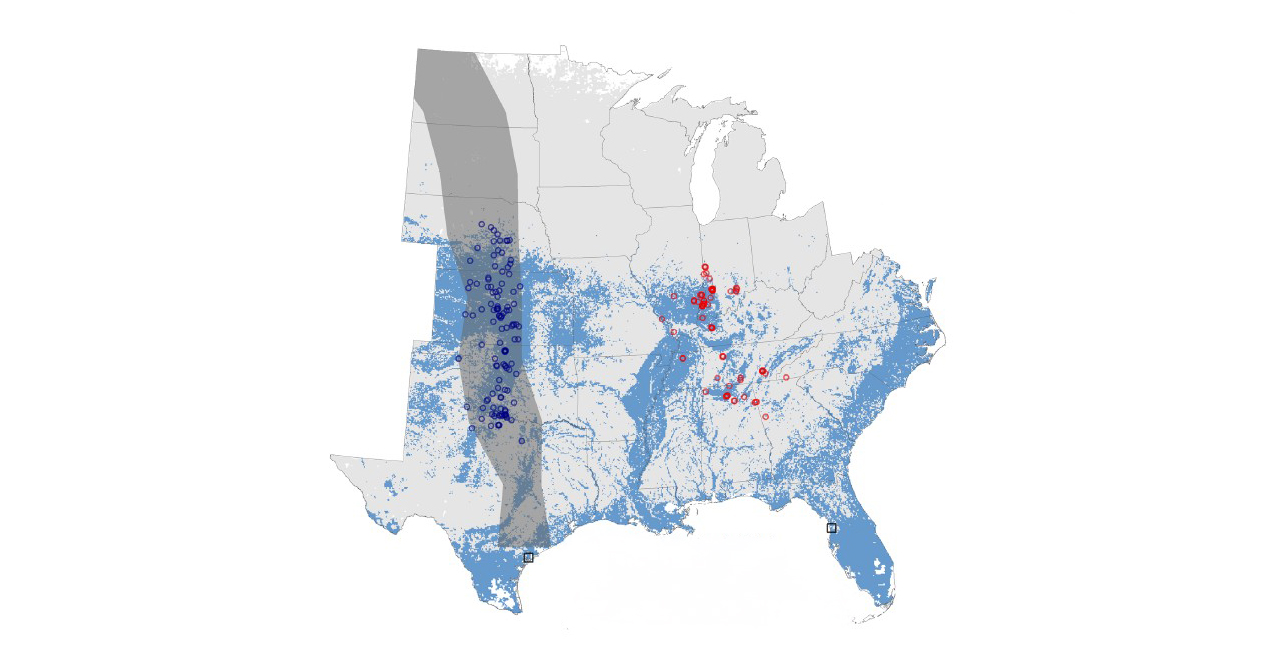

In contrast to the EMP, the AWBP has not shown any shortstopping behavior, and in 2023, researchers sought to determine the cause of this difference. They theorized that the lack of shortstopping in the remnant AWBP could be due either to a lack of suitable habitat or to social interactions between older, experienced birds and young birds learning to migrate. They used migration data from the EMP in a predictive model to assess causes of shortstopping. They identified that the presence of wetland habitat, grain cover, and above-freezing temperatures were the most important habitat characteristics of suitable wintering grounds. The same model was then applied to a map of the Central Whooping Crane flyway (Figure 1). The model identified that over 31% of the Central Flyway is suitable wintering habitat, and many of the sites where Whooping Cranes rest on their way to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge had suitable conditions for overwintering, yet they continue to migrate further south. If lack of available habitat isn’t the problem, why don’t we see shortstopping in AWBP Whooping Cranes?

Figure 1. Map of habitat that would be suitable for Whooping Cranes to overwinter. Blue: Suitable wintering habitat, Dark Grey: AWBP migration corridor, Red Circle: Actual EMP shortstopping sites, Blue Circle: Potential AWBP shortstopping sites, Black Square: Original wintering sites. Mendgen et al. 2023

One potential explanation for the discrepancy in shortstopping behavior in Whooping Cranes is the difference in rearing methods between the two populations. Juvenile Whooping Cranes in the historic AWBP, which are hatched and raised in the wild, spend the first year of life with their parents and learn the migration route to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The EMP, on the other hand, has many chicks that are raised under human care and then released into the wild in autumn, where we hope they will follow wild, adult Whooping Cranes.

To examine this difference, researchers calculated the average distance between wintering juveniles and the closest adult; this distance represents the strength of social bonds between birds. About half of the juveniles in the EMP wintered close to an adult (an average of just over one mile), which is comparable to most juveniles in the AWBP, while the other half wintered far from an adult (an average of 84 miles). Interestingly, EMP juveniles that wintered near an adult had significantly less distance to migrate by an average of approximately 250 miles. This indicates that shortstopping manifests later in a Whooping Crane’s life, once individuals have more knowledge of winter conditions in the greater migration corridor. The juveniles that winter near these adults learn shortstopping from them. Our observations of EMP juveniles wintering farther from knowledgeable adults suggest weaker associations and social bonds among EMP birds than in AWBP.

Through predictive modeling, researchers learned that the lack of shortstopping behavior in the AWBP migration corridor is likely not due to a lack of suitable habitat. However, habitat modeling is not perfect, and this model doesn’t account for wetlands that are only present seasonally or for differences in habitat requirements between the two migratory populations. This research indicates that social structures between cranes play an important role in shortstopping. Compared with the remnant AWBP, far fewer juvenile cranes winter with adults in the EMP, suggesting that social transmission of migration behavior is less prevalent in the reintroduced migratory population. In the AWBP, this tradition and established migration behavior could lead to fewer new behaviors, such as shortstopping. In the EMP, on the other hand, some individuals may learn more through experimentation and exploration rather than wintering with adults.

EMP Whooping Cranes in a harvested corn field. Cranes often forage in agricultural fields, particularly for waste grains left after harvest. International Crane Foundation photo

Overall, this study tells us that environmental and social factors might both need to be considered as causes for shortstopping behaviors in the EMP. The remnant AWBP has a long history of migrating to coastal Texas, with rigid social-learning structures that limit its flexibility in finding new wintering habitat, unlike the reintroduced EMP. Studies like this aid our work helping Whooping Cranes across North America by increasing our understanding of both migrating flocks.

Story submitted by Sophie Pedzich, Alabama Outreach Program Assistant, International Crane Foundation.

References:

Mendgen, P., Converse, S.J., Pearse, A.T., Teitelbaum, C.S., and Mueller, T. 2023. Differential shortstopping behaviour in Whooping Cranes: Habitat or social learning? Global Ecology and Conservation 41.

Published February 17, 2026