Why Do Whooping Cranes Migrate?

A pair of Whooping Cranes on their wintering grounds in Florida. Karen Willes

Whooping Cranes are one of many species that form strong bonds with their partners, and once that bond is established with another crane, they will typically remain in that pairing for life. However, it is not unheard of for Whooping Crane pairs to split for various reasons. One such instance was recorded in 2011 when a female Whooping Crane in the Eastern Migratory Population separated from her mate while wintering in Florida, where she picked up a new mate, a male Whooping Crane from the Florida Non-Migratory Population. This uncommon instance led to the first recorded roundtrip long-distance migration by a Whooping Crane in one season, which poses the question – what is truly driving crane migration?

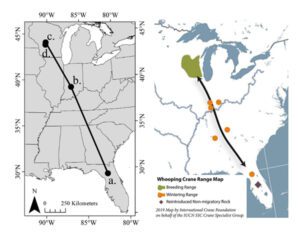

For Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population, fall migration is a part of their yearly routine. This behavior is believed to be stimulated by shortened days that come with changing seasons or an increased appetite. For some, this means flying down to Florida for the winter season. In the fall of 2010, 19-05, a five-year-old female Whooping Crane, flew south to Alachua County, Florida, for the winter alongside 8-04, the six-year-old male Whooping Crane she had nested with for the previous three years.

While in Florida, the female met 1343, a male Whooping Crane in the non-migratory population. Earlier that same year, this male nested with a female in the same non-migratory population, but following her death in 2010, he had not found a new mate. When the two Whooping Cranes overlapped in Alachua County, the female decided to stay behind with the new male. She left her previous mate to undergo spring migration to their northern breeding grounds alone. As the end of spring approached, the new pair flew north en route to the female’s breeding grounds in Wisconsin – and thus began the inaugural migratory journey of the Florida male.

So, what drove this previously non-migratory male Whooping Crane from Florida to migrate north for the first time? The authors of this paper (Szyszkoski and Thompson 2022) attribute it to a learned behavior driven by the need to breed. A similar example was recorded when a hand-reared, reintroduced, Red-crowned Crane changed migration routes and its normal wintering area after it found a mate who used a different flyway.

Additionally, this behavior of non-migratory cranes completing long-distance movements has also been observed in other Whooping Crane populations. For example, two males from the Louisiana Non-migratory Population traveled north into southern Canada in the spring of 2017, and seven individuals from the same population moved laterally to Dallas, Texas, in the spring of 2013, returning to Louisiana in the fall. What sets the Florida male in 2011 apart from the other cases, however, was the decision to fly back south that same spring.

As mentioned previously, fall migration is believed to be stimulated by shortened day lengths or increased appetite, but what was the motivation for the southward spring migration from the Florida male? After journeying north and arriving in Wisconsin, the female returned to her previous mate and former breeding grounds, leaving the Florida male without a mate or territory in an unfamiliar location. So, after 12 days spent in Wisconsin with no luck in maintaining the short-lived bond between the female and the new male, the male traveled back to Florida, thus concluding the 4,451km journey roundtrip in one season. This southbound spring migration, while odd, is believed also to have been driven by a need to breed. Following losing a potential mate, the male may have been driven by the desire to fulfill that need back in his breeding grounds in Florida.

The Florida male did not repeat this behavior in the following years. But by monitoring Whooping Cranes across their flyway and recording this behavior, our team of scientists at the International Crane Foundation helped gather valuable information about the drivers of long-distance movements and Whooping Crane cognition and decision-making regarding the desire to breed and the potential impacts of overlapping populations. This information is useful for crane conservation because understanding the drivers of migration and how the behavior is learned can help inform our reintroduction efforts for juvenile Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population, who are learning to migrate for the first time, and future reintroduction decisions for both migratory and non-migratory populations.

We thank Eva Szyszkoski and Hillary Thompson, the authors of the summarized manuscript “A roundtrip long-distance movement within one season by a non-migratory Whooping Crane (Grus americana),” for permission to share their work.

References:

Szyszkoski, E. K., Thompson, H. T. (2022). A roundtrip long-distance movement within one season by a non-migratory Whooping Crane (Grus americana). Wilson Journal of Ornithology 134(1): 97-102.

Mirande, C. M., Harris, J. T., editors. (2019). Crane Conservation Strategy. Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA: International Crane Foundation.

Story submitted by Travis Roddy, Whooping Crane Outreach Program Assistant, and Stephanie M. Schmidt, Whooping Crane Outreach Coordinator, International Crane Foundation