Natal Dispersal and Whooping Crane Conservation

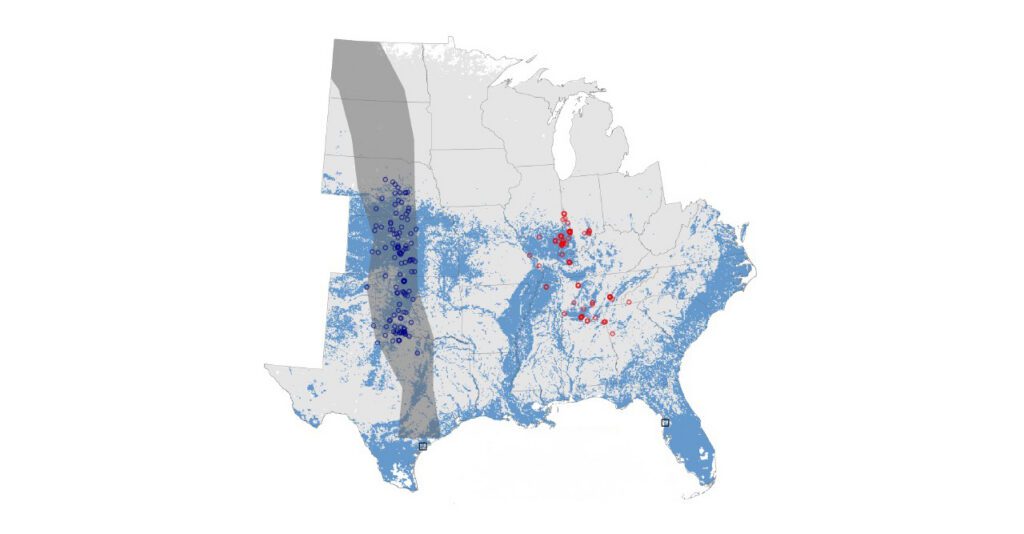

Whooping Cranes, once nearing extinction in the 1940s, currently number over 700 in the wild across four populations, thanks to strong conservation and reintroduction efforts. These populations are closely monitored by biologists who record their hatches, mortalities, population sizes and more as their numbers grow.

One lesser-known variable that the biologists at the International Crane Foundation study is natal dispersal distance, or the distance between where a chick hatches and where it nests for the first time after reaching breeding age, typically between four to five years for Whooping Cranes. Understanding natal dispersal allows biologists to predict better where Whooping Cranes may nest in the future to make more informed management decisions and proactively protect the habitats Whooping Cranes use while nesting. Additionally, understanding where a Whooping Crane might go and how far they may travel to nest can also help determine where young Whooping Cranes raised in captivity should be released into the wild to maximize their success at finding a mate and establishing a safe breeding territory once they are old enough to mate.

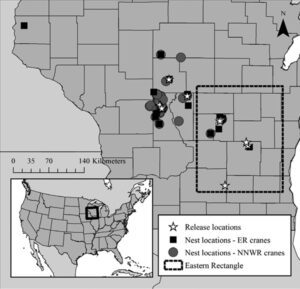

To ensure we make the most informed management decisions, our biologists at the International Crane Foundation and our partners examined the natal dispersal distance for Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population from 2005 to 2019. Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population breed in Wisconsin, primarily at Necedah National Wildlife Refuge or an area called the Eastern Rectangle, which includes Horicon National Wildlife Refuge and White River Marsh State Wildlife Area. In this study, we examined factors that often impact natal dispersal, such as the Whooping Crane’s sex, their natal location, where the chick was hatched or released, and whether the Whooping Crane was hatched in the wild or captivity.

Ultimately, we found that nest location had the greatest impact on how far young Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Migratory Population would disperse. For example, the average dispersal distance for a young Whooping Crane was about 17 miles. However, Whooping Cranes raised in the Eastern Rectangle tended to disperse about 50 miles, while those at Necedah National Wildlife Refuge had an average dispersal distance of nine miles. We even observed several Whooping Cranes raised in the Eastern Rectangle disperse to Necedah National Wildlife Refuge, where they eventually established their breeding territories.

So, what does this all mean? We believe this difference in dispersal distance is likely due to habitat type and quality at their hatch site. Necedah National Wildlife Refuge is a large, continuous sedge meadow wetland with minimal human development and disturbance. In contrast, the Eastern Rectangle comprises several isolated wetlands intermixed with private property and agricultural fields. Due to these differences in habitat type and continuity, Whooping Cranes in the Eastern Rectangle may have to travel farther to find a mate and suitable nesting habitat. Additionally, our scientists found that natal dispersion distance can also be affected by the density, or number, of territorial breeding pairs in one area. Whooping Cranes establish and defend large territories, and as more territories in a wetland become claimed by a pair of Whooping Cranes, there is less space for younger birds to establish territories and the further they need to travel to find available habitat.

These findings may impact future conservation efforts for Whooping Cranes. As the Eastern Migratory Population of Whooping Cranes grows, it is important that we continue to monitor what habitats Whooping Cranes are using, how far they need to disperse to find available quality habitat, and what factors are impacting natal dispersal distance. For example, while our study found that the hatch site was the primary driver for natal dispersal distance, other variables, such as male vs female dispersion and how this impacts future nesting and reproduction, may become important as the population grows. Understanding changes to natal dispersal distance and the factors that cause these changes will be important information for guiding management actions such as how much nesting habitat Whooping Cranes may need, where Whooping Cranes may go to nest, and where captive-raised chicks should be released into the wild to ensure they will be able to find a mate and a nesting territory.

We thank Hillary Thompson, Andrew Caven, Matthew Hayes and Anne Lacy, the authors of the summarized manuscript “Natal dispersal of Whooping Cranes in the reintroduced Eastern Migratory Population,” for permission to share their work.

References

Thompson, H. L., Caven, A. J., Hayes, M. A., & Lacy, A. E. (2021). Natal dispersal of Whooping Cranes in the reintroduced Eastern Migratory Population. Ecology and Evolution, 11, 12630–12638. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8007

Story submitted by Lauren Benedict, Whooping Crane Outreach Program Assistant, and Stephanie M. Schmidt, Whooping Crane Outreach Coordinator, International Crane Foundation