Connect with Whooping Cranes

Whooping Cranes are named for their loud, “whooping” call. Whoopers are described as large, bright white birds that move majestically through wetlands, grasslands and the occasional crop field. Whooping Cranes are monogamous, meaning they choose a mate for life, and perform an elaborate courting dance as breeding pairs. Their diet consists mainly of plant tubers, crabs, small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, insects and waste grain.

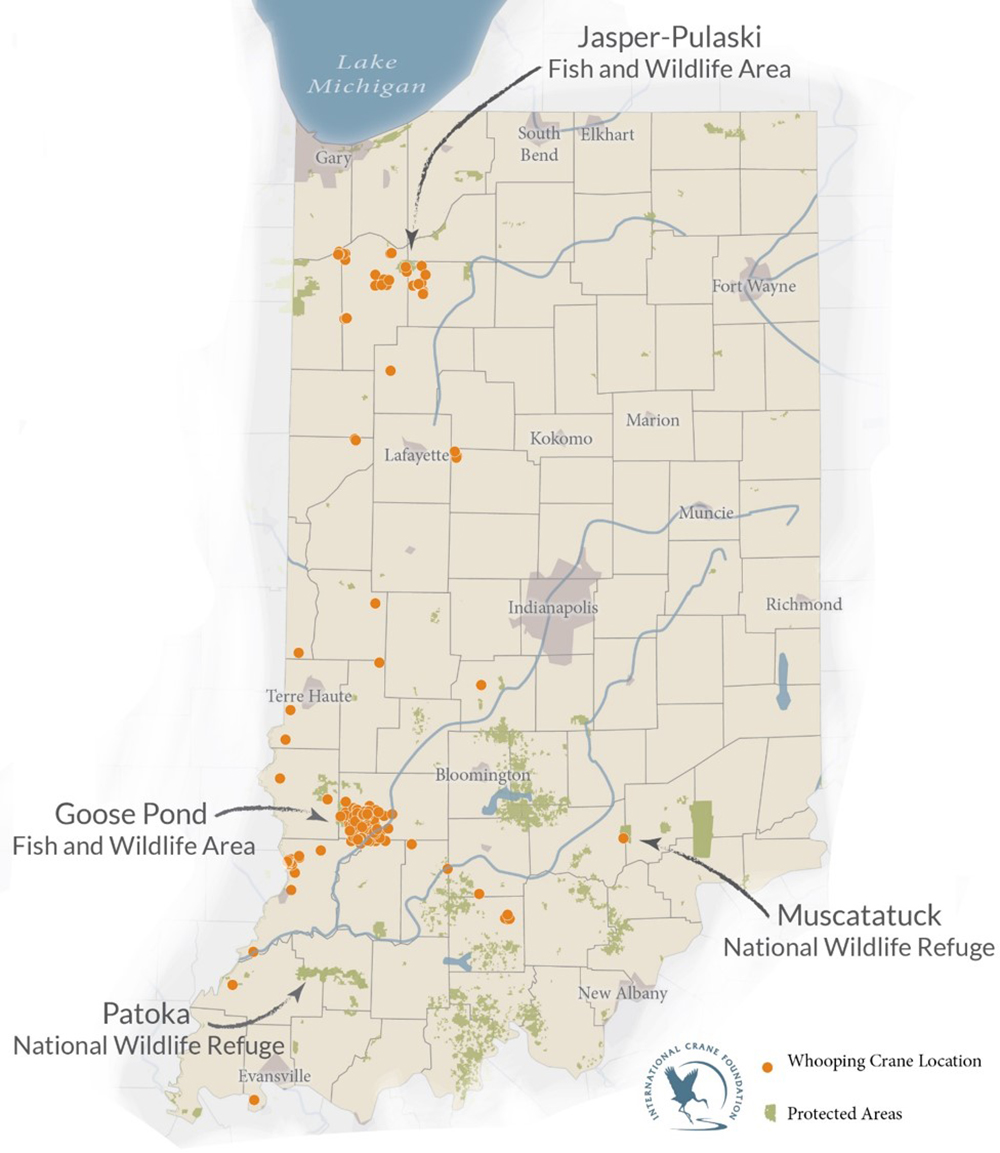

There are two distinct migratory populations of Whooping Cranes. In Indiana, we see the Eastern Migratory Population, which breeds in Wisconsin in the summer. Then small flocks fly south to their wintering grounds in the southeastern United States, stopping over in a few locations within Indiana. A few of these birds might spend the majority, or all of the winter, in Indiana.

The above right map highlights the public locations where Whooping Cranes migrate through Indiana. This includes the Jasper-Pulaski Fish and Wildlife Area in the northern half of the state and Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area, Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge and Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in the southern half of the state. Click on both maps to enlarge.

Goose Pond Fish and Wildlife Area in southern Indiana is a wintering area for Whooping Cranes that don’t migrate further south for the winter. Pictured is a Whooping Crane juvenile released at Goose Pond in 2019.

Whooping Cranes are federally listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, which means this species is imperiled and could become extinct. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service administers the Endangered Species Act and ensures that listed species are protected. The main threats to Whooping Cranes include loss of critical wetland habitat, low genetic diversity, power line collisions, predation, disturbance of nest sites and illegal shootings.

Please explore Ways to Help to learn how you, no matter who you are, can help save the Whoopers in Indiana!

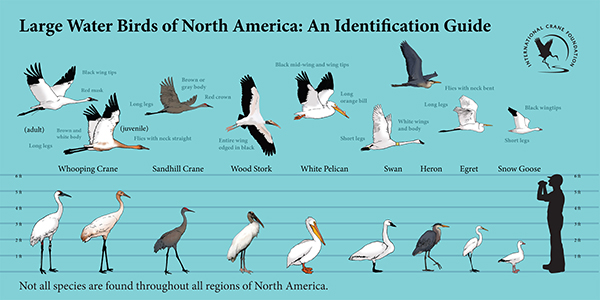

Can You Identify a Whooping Crane?

Whooping Cranes are often confused with other migratory, wetland bird species. So here are some tips and comparisons to help you tell them apart.

Adult Whooping Cranes are the tallest bird in North America! They stand at 5 ft tall with a 7 ft wingspan and weigh in at a whopping 15-17 lbs. These endangered birds can be distinguished from other large white birds by their black mustache, red featherless patch on their forehead, black legs, black wingtips (only visible in flight) and of course their impressive stature!

The Story of Whooping Crane Conservation

Whooping Cranes were distributed across a wide swath of North America into the mid-1800s, with population estimates ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 birds. With the migration of settlers westward, encouraged by the Homestead Act of 1862, much of the Whooping Crane native prairie and wetland habitat was converted to agricultural land. At the same time, hunting this species for meat, feathers, museum specimens and egg collection increased. As a result, there was a sharp decline and the near extinction of the species by the early 1940s. The total population of Whooping Cranes reached a low of between 20 and 30 birds in the 1940s and again in the 1950s.

Due to the critically low number of birds in the wild, a captive breeding program was established in 1967 at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland. The first captive eggs were produced in 1975 with the hope of reintroduction into the wild. Unfortunately, biologists realized the chicks imprinted on the people caring for them immediately upon hatching. These chicks unfortunately never learned to find another Whooping Crane for mating. It wasn’t until 1985 when biologists at the International Crane Foundation developed a rearing costume which consisted of a white suit with a crane puppet on one hand, as a potential solution to the imprinting problem.

In 1989, biologists decided to split the captive Patuxent flock to lower the risk of losing the entire captive population due to disease or storms and send half of the flock to the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin. Within a couple of years, the transferred cranes were producing eggs.

In the early 1990s, the first chicks born in captivity and raised using the costume rearing method were reintroduced to central Florida, where they successfully mated and produced a wild Whooping Crane chick in 2000. With the successful reintroduction in Florida, the International Crane Foundation, guided by the U.S.– Canadian Whooping Crane Recovery Team and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was interested in establishing an Eastern migratory flock, but the cranes had to be taught to migrate using technology previously developed to teach baby geese to migrate. The team partnered with Operation Migration, an organization that had volunteer ultralight pilots who wanted to help conserve endangered species. Operation Migration began training Whooping Crane chicks to follow ultralight aircraft driven by a pilot dressed in a full crane costume. Once the Whooping Cranes were ready to fly, they began their 1200-mile migration journey to Florida, with well-orchestrated stops planned along the way to refuel.

Through an intense human effort, the Whooping Crane reintroduction program has been slowly increasing the wild population of Whooping Cranes, and as of December 2018, there are approximately 849 Whooping Cranes in the world. Learn more about the efforts behind Whooping Crane conservation in the Whooper Timeline.

One of the BEST ways to continue to support Whoopers is to support wetland conservation! Historically, Indiana has lost 85% of its wetlands, which humans and animals alike depend on. Indiana is tied for 4th place in proportion of wetland acreage lost – and this is not a competition we want to win!

To find out more about historic wetland loss and programs that are already in place to help improve our wetlands go here.

You should also participate in local elections! Learn what the candidates support and advocate for the wetlands that we all require for a healthy Hoosier lifestyle. Find your legislators.