Raising Cranes

What does it take to raise a crane in captivity? Experienced and dedicated staff, healthy cranes and time. When any species is first brought into captivity, it takes trial and error to figure out how to keep them healthy and reproduce successfully. However, when wild populations are at great risk, such as with the Whooping Crane, captive breeding is an essential part of saving an endangered species from extinction.

We select Whooping Crane pairs based on each bird’s genetics, behavior, age and rearing history to create the best match. Due to the Whooping Crane’s low population in the 1940s (down to just 21 birds!), genetics play a very important role in the matchmaking process for this species.

Step 1: Matchmaking

Once individual cranes are identified as a “good match,” the socialization process begins. Socializing a pair can vary in length from a few months to several years based on the birds’ initial reaction to each other. The formation of a strong pair bond is critical because often a female will not be able to produce eggs until she has formed a strong bond with her mate. The Whooping Crane pair pictured above, Achilles and Aransas, took over three years to socialize and became a very genetically valuable pair.

Initial socialization sessions are brief and monitored closely by our staff via remote cameras. We look for synchronized preening, roosting, dancing and unison calling. As the birds become more comfortable with each other, elements are introduced that the cranes may exhibit aggression over, such as food and water. If the birds are interacting well, they are left together overnight. If they continue to get along after their first night together, they may remain together permanently. Our staff continues to monitor the pair, especially as the birds come into their first breeding season together.

GEORGE AND TEX

In the mid-1970s, a young female Whooping Crane named “Tex” represented the future of the species. She was the only surviving chick of a pair taken from the wild when the population was very low. Biologists working with Tex knew that she likely had rare genes found in no other Whooping Crane – genes that might help future Whooping Cranes fight off disease or adapt to new conditions.

But human-reared Tex was hopelessly bonded with people and would not pair with another Whooping Crane. How did we get Tex to breed? View our video for the answer!

LEARN MORE

Step 2: Eggs!

For Whooping Cranes, the breeding season begins in mid to late-April and continues through early June. Whooping Cranes typically have two eggs per clutch, with the second egg laid two to three days after the first. In the wild, a pair will attempt to hatch and raise both eggs. However, in captivity we have the option of multiple clutching – our staff removes eggs from the nest as they are laid or as a clutch is completed. By removing their eggs, a pair is stimulated to produce another clutch, thereby increasing the number of eggs that our flock produces. As a result, a single female may lay two, four, or even more eggs during a breeding season. Our staff looks at an individual female’s age, health and laying history to determine the number of eggs each crane safely can lay.

By the time breeding season arrives, our staff is preparing to begin artificial insemination on many of the pairs. This technique is used to manage genetic diversity and to increase egg fertility. Since we can do insemination on individuals from different pairs, strongly bonded pairs can remain together even if they are not a good genetic match. Insemination can also result in higher fertility rates than natural mating, such as with birds with clipped wings or arthritis that may have difficulty mating naturally.

Once the desired number of eggs has been reached for our captive breeding goals, we give many of our Whooping Crane pairs the opportunity to incubate their last clutch of eggs. This not only stops the female from producing more eggs but also serves as another pair-strengthening experience.

In order to successfully incubate all the Whooping Crane eggs collected through multiple clutching, we often use pairs of other crane species as surrogate incubators, including Siberian, Red-crowned, White-naped and Sandhill Cranes. These other species gladly accept the eggs and are generally more effective at incubating than machine incubators.

Most Whooping Crane chicks hatched at the International Crane Foundation will be released into the wild. Chicks that are genetically valuable may become part of our captive breeding population. In addition to the International Crane Foundation, facilities with Whooping Crane captive breeding programs include White Oak Conservation Center in Florida, Dallas Zoo and San Antonio Zoo in Texas, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Virginia, the Freeport-McMoRan Audubon Species Survival Center in Louisiana and the Calgary Zoo, Calgary Canada.

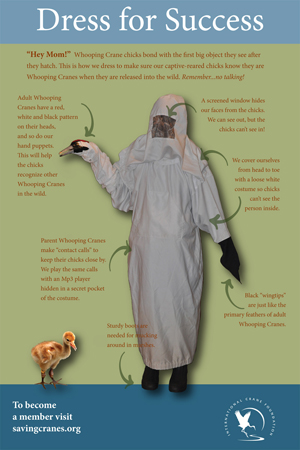

Chicks raised in captivity may be reared by adult Whooping Crane pairs or by our staff, who wear full-length crane costumes to hide the human form while working with the young cranes (click here to learn more about how we “Dress for Success”). We use this costume-rearing technique to make sure the chicks imprint on Whooping Cranes (the costume and hand puppet mimic the colors and shape of an adult crane) and are prepared for life in the wild.