Since the reintroduction of Whooping Cranes into the Eastern United States in 2001, researchers have carefully tracked the survival and success of the Eastern Migratory Population (EMP) population. Reintroductions are a powerful conservation tool but can be costly and require careful management. They are also very time-consuming, as we see with the EMP, whose growth over 20 years later still depends on continued releases of captive-reared chicks. As of August 2024, the estimated population size of the EMP is 68 individuals.

In 2022, researchers evaluated the status of the Whooping Crane reintroduction over the past 20 years to summarize the successes and struggles or threats the population faces across their range and look for long-term trends. Such summaries are important milestones in a reintroduction, connecting key information that will guide conservationists’ efforts to secure the future of the EMP.

Reports such as these would also be impossible without long-term monitoring efforts and extensive knowledge of individuals in the population. All Whooping Cranes in the EMP are banded with a unique color combination, allowing us to identify and re-sight birds throughout their lives.

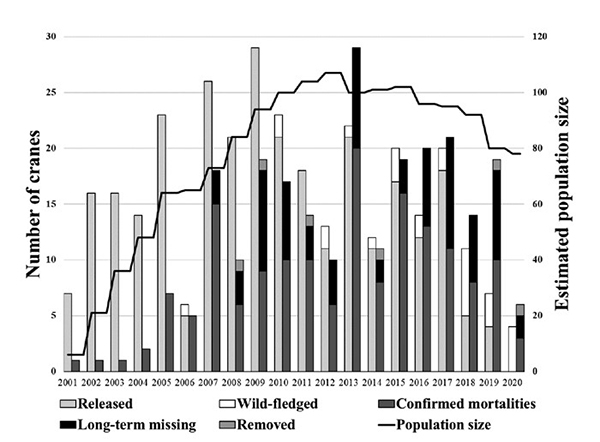

This study found that over the past 20 years, the overall population trend has been positive. There has been a slight decrease in the population size since the mid-2010s due to changes in our release efforts, but we have also seen more wild chicks surviving to adulthood. While making sense of these trends, researchers also took stock of factors that impact population size over the years, including causes of mortality. Of the mortalities in the EMP where the cause of death could be determined, the most common cause was predation, which accounted for 54.1% of known mortalities. Other common causes were impact traumas (i.e., collisions with powerlines, vehicles, or aircraft), disease, and poaching.

In addition to reporting the trends we are seeing, the International Crane Foundation has been learning from this information and adapting and improving our methods, including our rearing techniques, which have shifted towards more natural methods over the past 20 years. This includes prioritizing parent rearing, where a chick is raised in captivity and taught necessary behavior by a Whooping Crane role model under human supervision, over costume rearing, where an aviculturist in a Whooping Crane costume teaches chicks necessary behaviors for survival in the wild. Another change in the rearing program took place in 2016, when the ultralight program ended. The ultralight program aimed to teach captive-reared Whooping Cranes to migrate to Florida for the winter by leading them with a piloted ultralight aircraft. Once this was achieved, the chicks released in the following years learned their migration routes from older cranes in the population.

Our team has also needed to exhibit flexibility in a changing landscape over the past 20 years. This was necessary after our breeding partner, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, ended their Whooping Crane program in 2017 and again in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic halted captive-rearing and release efforts. Luckily, the rearing and reintroduction team has also grown over the past 20 years, and they continue to provide high-quality care to Whooping Cranes to prepare them for release, backed by the most up-to-date science.

Management of the Eastern Migratory Population has also needed to adapt over the past 20 years as the range of the wild population has slowly shifted north. For many years, most Whooping Cranes in the EMP spent their winters in Florida, where the ultralight birds were taught to fly. However, today, the largest proportion of wintering Whooping Cranes in this population can be found in southern Indiana and northern Alabama. A few proposed explanations for this trend are warmer winter weather, the phasing out of the ultralight program, the availability of resources on northern agricultural lands, and younger cranes following older cranes to more northern wintering sites. It will be interesting to see if and how their range shifts in the next 20 years, but in the meantime, conservationists are reacting to this observation and working to secure critical habitats for Whooping Cranes across their entire flyway.

Looking back much has changed since Whooping Crane reintroductions began in the eastern United States in 2001. Over the past 20+ years, this population has been the focus of extensive monitoring, research, and management, and they have given us key insights into solving the puzzle of Whooping Crane conservation.

We thank the authors of the paper “Twenty-year Status of the Eastern Migratory Whooping Crane Reintroduction,” Hillary Thompson, Nicole Gordon, Darby Bolt, Jadine Lee, and Eva Szyszkoski, for permitting us to share their work.

Story submitted by Alicia Ward, Crane Conservation Fellow, and Stephanie M. Schmidt, Lead Outreach Biologist, International Crane Foundation.

References: Thompson, H.T., Gordon, N.M., Bolt, D.P., Lee, J.R., Szyszkoski, E.K. (2020). Twenty-year Status of the Eastern Migratory Whooping Crane Reintroduction. Proceedings of the North American Crane Workshop 15:34–52.